World Records for Blue Marlin

Wendell

Ko

World record for Blue Marlin, Wendell Ko—506 pounds

(229.7 kilograms), Kona, Hawaii, November, 20, 2013

Wendell

Ko—World Record Pacific Blue Marlin

I've

often wondered what it would be like to come face to face with a beastly marlin in the

ocean, a competing predator with a spear of its

own more primitive than mine. I've thought of

the many scenarios in the event of an encounter with the behemoth, and weighed the

consequences of a battle should it occur. If I

failed, I could ultimately die. The

episode has been played and replayed, over and over in my mind with varied scenarios. And in each situation I make the right choices and

leave no errors for mistakes. But I've come to grasp that although I take all precautionary

measures in subduing a giant, the event could still be costly. There is no question that our ocean is wild and

full of danger, but she can also be a great educator, lavishing wisdom to teachable

students. And if one is careful to give her

the respect that she deserves, one can learn much.

I have chosen to learn.

Most

of my hunting is focused in waters beyond our

reefs; at FADs, in bird piles and deep

drop-offs, in waters where the ocean floor is rarely seen.

It is often a quiet and desolate place.

There I become enveloped by infinite space, detached and vulnerable. There are no boulders, crevices or caves to conceal

myself. Yet somehow I feel at home and at

peace with my surroundings. In the quiet

solitude my senses become sharp and my awareness keen.

On single breaths at a time I hover at depths of neutral buoyancy, loosely

tethered to a line that keeps me from sinking into the abyss. I want so desperately to see magnificent creatures. And I desire for them to see me. My arrow is locked and loaded, and ready to unleash

its fury at a twitch of a finger. But most of

the time the arrow remains fixed, a fish swims by, and no life is taken.

This

time however, near a buoy outside Miloli'i, I chose to take the fish. It was the beast in which the engagement I've

pondered time and again, my top ocean competitor; Makaira

Nigricans, the pacific blue marlin, or A'u. I

had come prepared for the battle. But the

battle wasn't all that I've imagined it to be. I imagined a long duel of deadly weapons with no

codes of conduct, an all-out bloody war. Here before me suddently appeared a mammoth fish, a worthy opponent of

terrible stature; more than twice my height

and three times my weight. He approached me

with his sword upright and his mouth agape,

advancing boldly and aggresively. This is it,

the moment that I've prepared myself for. I

was ready. But my gun was unloaded.

We

were laboriously hunting in large schools of aku and shibis for two hours, but with no

signs of bigger game we took a short lunch break to refuel and reenergize our bodies. As we rested on our 28-foot Radan captained by

Nathan Abe, we watched a few boats hooking the smaller game.

We discussed our game plan and agreed to put in another hour. First to jump in, Puna decided to take his less

powerful gun to spear the tuna for sashimi. Tempted

to do the same, I decided instead to stay fixed on my goals and continued hunting the

phantom fish. Almost into our final hour,

captain Nate noticed a big splash near the FAD and quickly notified us. We worked the FAD a bit longer and with no other

signs of the ghost we called it quits. We

unloaded our guns, Puna handed his to Ernie while I turned to take a last look around. What I saw, I couldn't believe. I yelled for Kyle who was passing up his underwater

camera while quickly loading three of four bands to my 66-inch custom blue water gun. I took a huge breath and made way towards the beast

when I noticed my slip-tip was not in place. Still

advancing underwater towards my target, I carefully made the necesarry corrections. He was not intimidated. Neither was I.

A worthy opponent indeed. I

sighted my spear too long without flight, and finally released its fury. It hit its mark perfectly, pentrating his neck. Everything from then on seemed to happen in a

fast-forward mode. I passed my gun to Puna and

held on to my 2-atmosphere floats, applying immediate pressure for about five breaths. I then released the floats and watched them whisk

away only to slowly come to a halt. Suddenly

the marlin broke surface. With such unforeseen

pride he paraded himself back towards me, tailwalking a quarter of his magnificent body

above water, while dragging my floats behind. I

grabbed my back-up 140cm Aimrite and met him below surface as he lowered his head. We met again eye to eye. Without hesitation I released another spear to

secure my catch, then watched him turn belly-up. I

then hesitantly reached for his sword in a gesture of gratitude to thank him for a quick

battle, and in a strange way to honor him. I

could still feel a bit of his life draining by grasping his bill and graciously released

him. I loaded a final spear, and with

indubitable respect finished him. The battle

orchestrated in my mind so different than the battle that actually took place. Still, I am grateful for the opportunity to be

blessed with this unexpected gift, and to have survived the event.

After

releasing air from its air bladder, turning the fish upright and a short photo shoot with

Kyle Nakamoto, I passed the bill to Captain Nate. It

took four of us to finally heave the fish aboard. It

was then that we all got a good look at its size, each of us estimating its weight. On our way back to the harbor, I reflected on the

whole event, and realized how privileged and honored we all are to have engaged in a rich

experience that will forever be engrained in

our minds. The ocean is my teacher and my

friend. And I thank the Creator of all

creatures great and small for the many lessons learned, protection always given, and the

undeserved gifts He so kindly bestows.

Coming

into Honokohau Harbor we met Captain Randy Llanes on the Sundowner who saw the fish from

his bridge laying out on our deck and handed us a tape ruler. We took a single measurement of 114 inches from its

lower jaw to the tail's fork and right away Randy called it "450 to 500 pounds

easy". We made it to the weigh station

where weighmaster Sunny and a small welcoming party

awaited us (news travel quickly at a harbor). When

the marlin was hoisted, part of its intestines fell through its mouth and into the water

below. Still, this pacific blue marlin was

truly a beast weighing 506 pounds and by far the biggest fish ever speared and brought to

berth in Hawaiian waters, and the pending IBSRC World Record.

We

celebrated its weight and its significance, and left the marlin with the people in Kona to

smoke and enjoy, besides we had our work set out in cleaning some mahimahi that we speared

on the previous day.

*******************************************************************************************

Calvin Lai Jr.

Previous World record for Blue Marlin,

Calvin Lai Jr—278.5 pounds (126.4 kilograms), Kona, Hawaii, December, 19, 2005

It was a Monday morning in Kona, a beautiful day and

another dive trip for my partners and me.

Getting off work from the fire station felt like eternity knowing that I would have a full

day in the water. I started to make my phone calls to my dive partners Domninic Gomes and

Uncle Ryan Koyanagi. Everything seemed fine until I started driving to the Honokahau

Harbor and saw white water breaking across the channel entrance. I called my dad who is

the captain on our boat, the CHELSIE ROSE and asked him if we were really going to dive

today. His response was, "No problem and hurry up—you're late!"

Everyone was feeling so excited as usual about a blue water trip and the possibility of

someone spearing something big. The typical conversation on our way out to the buoy is

almost always a ragging each other on who missed or lost their last mahimahi or ono.

Well, it was a little bumpy on this day and not the almost-always smooth Kona water. Our

first stop was at VV-buoy. Nothing there, so we did our usual run to the next buoy, which

happened to be C-buoy. Here we found aku and birds at the surface, but nothing to get

excited about. With too many boats in the area, we decided to leave. It was full throttle

to the next buoy! Full throttles yes! This boat has two speeds, idle and full throttle.

Betting impatient and excited, we headed to UU-buoy. Approximately 10 minutes after we got

there, Rob White and partner Garrett Nishihara came by and asked if they could jump in.

"Of course", we said, "No problem, go right ahead."

We then headed South to B-buoy. It was our last chance because the wind started to pick

up, Finally we were jumping in and getting our gills wet. It felt great, but there were no

mahimahi or one. We jumped back into the boat, ate lunch and discussed what to do next.

This wasn't our typical blue water weekly dive. Usually, everyone gets a mahimahi or two.

Saying it in a humble way, it's because we do blue water hunting at least twice a week and

if you spend more time in the blue water, eventually you will shoot something.

Driving back to UU-buoy, my dad said, "Hey, you should jump back in at this buoy

because there are no boats in the area.

It was about 2:30 in the afternoon and my dad dropped us off 150 yards up current. The

current was a little strong. My Uncle Ryan jumped in first with his daughter Amber with a

camera and my other partner Dominic jumped in as well. I was last in. One more try for the

big one--mahimahi and and ono usually, and anticipating big boys like sailfish, marlin or

even a large ahi.

With the floats out and guns at the ready, we drifted to the buoy--acting like a log,

waiting for something to appear until finally, we see the chain at the buoy. Wait! Is that

aku underneath the buoy all balled up and scared as hell? Yes it is! Wow! There is a

marlin circling the buoy--a blue marlin.

Getting closer, my heart starts to pound and my partner Dominic is there 20 feet in front

of me. I yell at him to take the shot. He looked as if he was 15 feet out, with the

current sucking faster as we approached. My partner did not take the shot and went past

the chain by the buoy and marlin. I could still see him trying to kick back and get a shot

off, but it was too late, he had drifted too far past the marlin.

I finally drifted to the marlin and tried to hold my ground as my float line and buoy

passed me. The marlin went around the buoy and came straight toward me down current with

its mouth open and, "oh boy", what a sight! This fish was so huge under water. I

felt like I was bait.

I held my position and waited for the marlin to turn broadside and it did. As I turned, I

had a point-blank shot at least 4 feet from the tip of my spear. I pulled the trigger,

aiming for the lateral line. Lucky as I was, I stoned the fish with one shot. It did not

even move! I saw the shaft go through the marlin and fish turned color. The shaft had

broke the fish's spine and exited about 8 inches on the other side.

The marlin was sinking and so did my float. It was going down slowly. Grabbing the float,

I pulled it up. when I got the fish up to 15 feet of the surface, I put a second shot in

it with my second gun. It was all over and all I heard was screaming and yelling from my

partners.

As I tried to swim and pull this marlin toward the boat, I grabbed my tagline and wrapped

it around the back cleat of the boat and we all pulled it in the boat. Estimating the

weight, we guessed 300-pounds or more.

What a sight!—having this large fish stretched out on the deck of our boat.We were

all laughing and hugging each other on the boat like we won a million dollars. Heading

back to the harbor, we arrived at Honokohau's weigh station and lifted this marlin up and

the digital, certified scale read 278.5 pounds. What a great day it was.

I couldn't have done it without this great crew: Dominic, Uncle Ryan and my Dad and my

boat. My dive partners are one-of-a-kind. Dominic could have put a shot into this marlin,

but held off on a fish of a lifetime. Anyone else probably would have launched this

less-than-perfect shot, perhaps wounding or losing the fish. Thanks Dom, yours is next and

I hope it's bigger than mine. Uncle Ryan, my other dive partner, is always there for moral

support. Mahalo! He just started blue water diving and shot his share of mahimahi and one.

Most of all, thanks to my dad who is retired now and is a full-time boatman for weekly

spearfishing trips with this wonderful crew. Also, last but not lease, thank you for the

pictures from your digital camera—Jessica Gomes and Amber Koyanagi. Thanks to the

Lord for keeping this crew safe on every dive trip and bringing us back home.

Aloha Calvin

*********************************************************************** |

Previous world-record blue marlin for men, Ken Chiocchetti—48.1 pounds (21.8

kilograms).

************************************************************************************

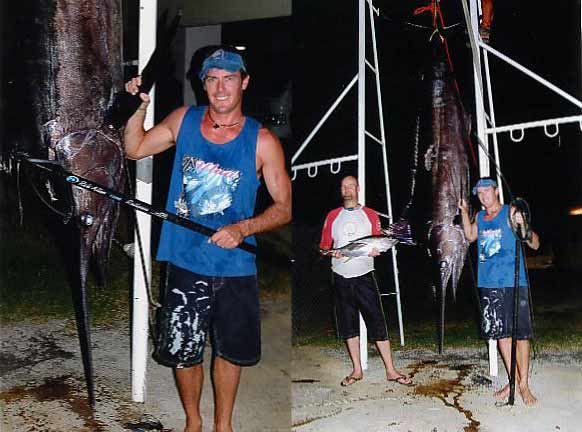

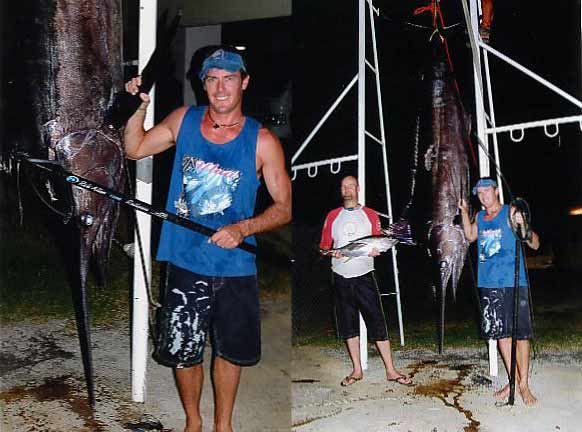

Meritorious award for blue marlin for

men, Anthony Honeybone—266.8 kilograms (587.6 pounds), Efete Island, Vanuatu, May 16,

2005

Anthony Honeybone

**********************************************************

Ian McGonagle

Notable blue marlin catch for men, Ian McGonagle—760 pounds (345.04

kilograms). by Ian McGonagle as told to Terry Maas

Recently, Ian McGonagle speared the largest gamefish ever landed by a freediver-a

760-pound blue marlin. Following a tip, Ian and Peter located a current break about 6

miles from shore said to hold 20-pound tuna. A male and a female friend accompanied the

brothers in their 16-foot skiff with its sputtering 30-horsepower engine. After diving for

a few hours, they returned to the skiff to rest. They'd seen small wahoo and unusually

skittish tuna-instead of swimming around boldly, the small tuna darted and streaked about.

At 4 p.m., the team made a final drift in the waning sunlight. Ian remembers:

I could see Peter and Chris in the distance, when suddenly a wall of bait and tuna came

rushing toward me. Three tuna broke from the school, one swam between my legs and the

other two tried to find shelter in my arm pits. I was busy trying to push one of the tuna

far enough away to get a shot with my long gun, when I noticed what provoked such unusual

behavior. It was a giant blue marlin, lit up like a neon sign with brilliant blues and

golds.

One tuna remained as the marlin made several passes in front of me. After what seemed like

minutes-but was probably 30 seconds-I fired, hitting the fish in the shoulder area.

My float streaked away like a missile. I yelled for the panga. Peter, who was hunting 100

feet away, heard my big Prodonovich gun fire. The marlin shot by him towing my float

behind. "That thing was huge," Peter exclaimed. "It looked like a rocket

going by, lit up like Las Vegas." The fish wore neon green and purple-blue bars

dancing with pulsating spots of color traveling up and down its body. Its tail made huge

4-foot sweeps.

We jumped in the boat and motored up-current in the direction of the missing float. When

we located the float, all we saw was 6 inches of the float's back end as it made its

steady way into the current.

I jumped in the water with a second float and quickly tied it to the first. For the next 2

to 3 hours, I was alternately pulling or being pulled. Sometimes I was forced to let go of

the line when the fish pulled too fast or went too deep. Peter, unaided by the towing

marlin, swam faithfully at my side for my protection. We knew that marlin sometimes turn

on fishing boats and spear them.

I tugged so hard that my mask fogged from the exertion. After covering 5 miles with me,

Peter took a well-deserved break in the skiff. My line, which constantly pulsed and pulled

at my hands, suddenly went slack. I wondered which of the weak points on my gear had

failed-the float line, wire cable, speartip or a crimp. When I turned, I realized that the

big fish had surfaced and was circling behind me, still glowing like a neon sign-except

for a dark spot where the spear lodged. Peter joined me just as the fish took off on its

final run. I pulled as hard as I could and the fish finally came up after 10 minutes.

I asked Peter to take a second shot to secure the catch. The fish turned bronze and

greenish blue, as it sank, lifeless. I swam up to the great marlin and tried to hug it as

if to say, "Thank you for such a wonderful battle." When my hands would not meet

on the other side of the fish, I realized that this marlin was indeed huge.

The way three men and a woman got this huge fish into their small boat in the darkening

waters is a study in determination. There was no way they were going to tow the big fish

in after dark. Three of them pulled ropes attached to its bill and tail while Ian

belly-hooked the fish with the gaff. On the count of three they rolled the big fish over

the gunnel. It must have been a surreal sight as the four hooted and screamed in the dusk,

gliding over the calm sea, the sides of the boat just inches from swamping. That night

they measured and cleaned the fish, finding a 25-pound tuna in its belly. After finishing

the filleting at 1 a.m. the brothers awoke early for the three trips into town required to

distribute the extra meat to the needy.

|